a common disinheritance

Mister, Mister was written between 2017 to 2022 – do you remember?

Five years when the narrative grounds began to shift. The spectres of Brexit, Trump and European far-right resurgence ripped seams asunder. The optimism of the previous decade was lost. The news of the world became consumed by ISIS videos, terror attacks, austerity measures, intelligence leaks, and the Syrian civil war. The migrant crisis provided a stream of daily tragedy. And you noticed, for a time, the discontent around border policy in the EU.

Do you remember watching the UK Conservative government strip rights away from British citizens? Those who’d left militant groups in Syria and returned home. How Shamima Begum and Jack Letts became household names for a time. And how refugees and returnees were imprisoned in detention centres across the country.

Were you stirred so early?

The part of you that couldn’t help but write into it.

That’s for any novelist, you’d like to claim. For any novelist already suckered in, already invested in the genius of the novel form. It felt necessary to write into the tattered narratives of Britishness, belonging, and the upheavals of both. For you, this meant writing into them frayed margins again. To focus on the ‘returnees’ in the news, repulsed and denounced as heretical.

Was there an affinity shared with the likes of Shamima Begum? Had you heard some faint possibility in her voice?

More likely a common disinheritance. A marker of diasporic strife – a feeling within and fumbling forward, between locales and slippages in speech – which manifests itself always as an incongruity.

You’ve felt that incongruity as a British citizen. But also in the idea of yourself as a British novelist. At once in excess and limited to the personal or political. You had to breach both lines to write anything worthwhile.

borders, bodies - imagined and material.

It’s around 2018. The migrant crisis and the Syrian civil war continue to disorder the national psyche. Do you remember noticing how newly confident quarters used the media parade of darker-skinned bodies to partition away belonging? Them ones wagging flags in a frenzy. As if cornered. As if letting go of a tired leash, saying what needed to be said, words only meant to hold, tighten, and reaffirm certainties.

They questioned – but truly they were demarcating, separating, normalising, in rabid public discourse – how a person ought to be treated. How the state ought to manage human beings as designations: citizen, foreigner, enemy of the state. And did you notice how the same lot conspired to cloud racial and gender difference, trans rights, the cost of living crisis, class, and free speech?

You might not have known it at the time, but this was what you had to write about: a crossing of lines in the open air, the crossing of borders. You had to write about how bodies transgress boundaries, both imagined and material.

yahya’s refusal

Back then, before the first miscarriage, you wanted your second novel to be about a father and son. It was a story stuffed with your interest in Sufi tradition. About written translation, speech and the relation between English and Arabic poetry. You wanted to indulge yourself. Write into something felt but not entirely understood. It was to be a quiet book, something small. And yet, after so many drafts discarded, the novel demanded more than you felt capable of imagining.

How did Mister, Mister, the novel your readers hold, get to be? This noisy, blaring, maximal book. Like a salt-water refraction of the times.

This is what the back cover says: Mister, Mister follows the life and times of Yahya Bas. Yahya speaks to someone he only refers to as ‘Mister’. Yahya has returned to the UK from Syria, having made a name for himself as a poet-preacher. He finds himself in a UK detention centre accused of inciting crimes for which he has to answer. In order to explain himself, Yahya decides to tell his life story.

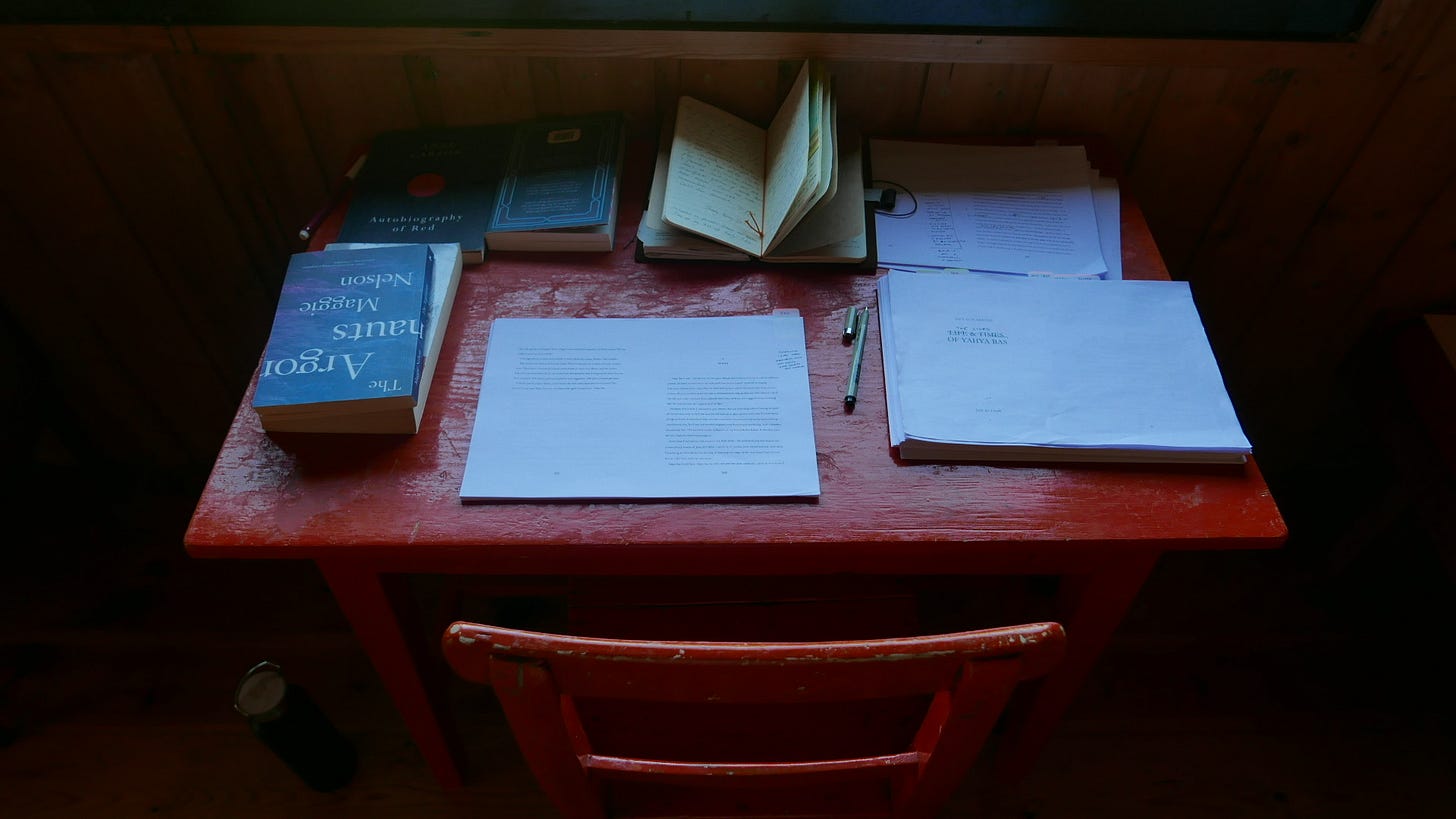

At first, your intent was more straightforward: evoke the epic picaresque patterns of the 19th-century novel. A modern telling set to a life and times adventure. Inspiration came from David Copperfield, Epigraph of a Small Winner, Great Expectations. You wanted to give a cock-eyed nod to them old turbulent recollections. Render an echo of Dickens in Yahya’s childhood. Raise the dead Brás Cubas from Machado de Assis. You wanted to summon Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March, a book that captured the first half of the 20th century so well. Yahya made you think of the fiendish yapping of Oskar too, another impish boy witnessing history in Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum.

Your novel would draw from these roots. You wanted the story to proceed in a similar fashion: to illustrate the shaping of selfhood, the shaping of a person over time.

But then something happened.

It was Yahya who seemed to refuse you. He resisted your attempt to shape him. Yahya Bas, the accused returnee, disinherited citizen, orientated many ways, demanded opacity, and kept bending toward ambiguity and oscillation in the metamodern sense. He was like a kind of insurgent in his own story. The more you drove toward an edifying wholeness, the more you felt an agitated steer toward some further unravelling.

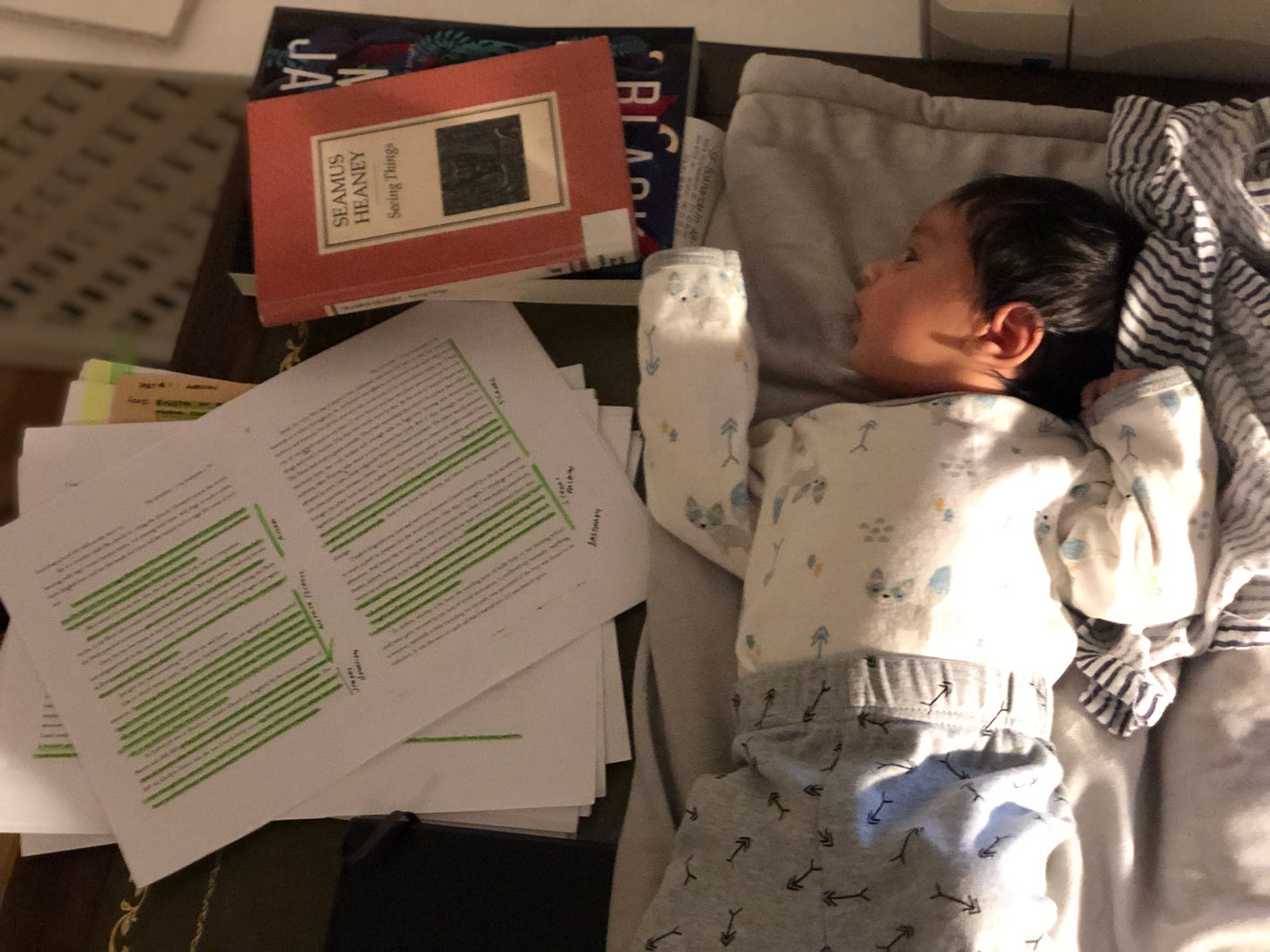

You tussled hard. Like years. But then your daughter was born, and you had little time to quarrel. So you gave in. You let it wander. You offered space on the page and let its central voice dance in mad procession. Countless drafts later, you can see how letting go mattered immensely.

The book needed to drive off its rails. The story became the grounds for excoriating identity. Having chosen a form so misappropriated by national myth in the past – the picaresque, the bildungsroman, the künstlerroman – what did you expect? Yahya’s voice could only ever work to undermine, evade, and spike convention.

You were exhausted. But your exhaustion would evolve into something revelatory, something vast, something inexplicable.

rhythms in bewilderment

This lasted a year. You resolved to follow Yahya through his journey. But in his squinted perspective, the world appeared suspicious. Filled with mirrored projections, treacherous masks, all part of a hostile schema that ascribes only caricature and cruelty to him. Identity for Yahya becomes a matter of semblances. Booby-traps to fall into, snagged and apprehended by, or a series of anonymised faces that could be slipped on and off whenever the opportunity arose.

Do you remember how bewildered you felt by all this? How Yahya Bas disputed, refused and outright reassigned the words ‘self’ and ‘sovereignty’?

Early in the novel, Yahya describes his body as near formless. Later, he begins to assume the shapes society holds for him – an Other, an errant, a monster. As he sheds one guise, he assumes another, remaining elusive, slipping our grasp, and escaping categorisation by extending into unbridled imagination. You learned to understand how self-definition for Yahya felt important, but his moves toward unbelonging, unmaking, and the dismantling of self, felt truer.

Eventually, you found a rhythm between Yahya’s expression and the rowdy decades in which the story is set. The 1990s would contain Yahya’s childhood. His several educations play against the early 2000s. His fame would come thereafter. And then his exile and eventual capture. Still, you felt that incongruity throughout. Yahya’s world was populated with characters shaped by surface idiosyncrasies. It felt like a cast of carnivalesques, typical for any 19th-century novel. Except Yahya Bas remained at its centre: indefinite, fragmented and modern.

There was something there, though. The juxtaposition excited you. You plunged into the re-inventions of Kathy Acker and her 1994 remix of Great Expectations. You re-read Virginia Woolf, novels pitched to the vivid lifetimes of Orlando and in The Waves. You convinced yourself that Sonallah Ibrahim had something to teach you in That Smell. Sadallah Wannous and Nawal El Sadaawi gave you confidence. You printed photocopied pages of the Hayy Ibn Yaqzan and spent money on courses in Arabic, and the foundations of Islamic philosophy. There was air in your lungs by then, the words were coming out strange, but coming. And somehow, all this nothing, nothing, nothing became everything.

consequences

Do you remember the year before that? Your zoom call with your editor and agent. Both were sympathetic, supportive and understanding. You broke down and shared your hopelessness. You felt lost, like nowhere. But you also found new thresholds in those moments. Heaped under so much loneliness and exhaustion. And you knew by then that there were parts of yourself that were splitting open.

Your face didn’t feel like your own. Neither did your body. There were times when you thought you were going mad drowning in that invented voice. In your rooms at Cambridge, you started bringing your laptop under the desk. You wrote about Abu Ghraib under there. Them American soldiers with their thumbs up. Small, and hunched, you wrote about terror and collapse. You wrote through Yahya’s pain until you got sick and continued elsewhere.

But then, but then: Yahya burned the photograph. Yahya fell into the barzahk. Yahya revives and divines new possibilities with Ester and Rustum in the guts of a devastated city. This is where you really were when you felt nowhere.

You understood Yahya’s impulse to siphon all that ugliness, violence and anger into incendiary poetry. He was inventing back at a world that desired to invent him first. A world that could only conceive of him in hateful dimensions. And so he invents again, invents in response, resolute in his rootlessness.

It was around this time that you read a lot of Glissant. You were reading Preciado. Wynter and Halberstam. And with your family’s blessing – another baby on the way – you were discovering new determinations as to how to be yourself. As disruptive as this period was for you, you can see how so much of it came through the writing. And those shifting realisations, with their hopeful and bewildering consequences, remain as echoes in this new book. Be grateful.

new availabilities of being

Audre Lorde, in her famous distillation, wrote in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name:

“If I didn't define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people's fantasies for me, and be eaten alive.”

You read that now and think: epigraph. It’s a description the stakes whenever we choose to play parts in other people’s myths. National myths, identitarian myths, dangerous myths that lead to hailing monsters, or the old Dickensian ones about bloodlines and buried fortunes. To break free of them all, to refuse, breach, and burst through – these are moves that suggest some ecstatic passage. That is what writing has taught you. It’s the only means by which anyone, including the likes of Yahya Bas, might discover what Glissant once described as ‘new availabilities of being.’

That’s where you left Yahya: in a new availability of being. A place to begin again. And it’s why, on the first pages of Mister, Mister, Yahya Bas is bloody-mouthed yet triumphant. He is recovering from his self-mutilation. He has cut out his own tongue. He’s unable to tell his story. But he can write it. And he does. Promising from his writing will come everything – his whole life.

This book rewrote parts of you. And you left them guessing on him. An idiot, a poet, a jihadist, a son – Yahya Bas might be all of these or none of these at once. Instead, he reaches for something else – invention, masquerade, and ruse. He reaches for a way to turn the language of identity against itself and set himself free.

Guy Gunaratne

2023